We were on a typical Sunday visit to Bridgeport, Stratford, actually, where Dad’s parents lived. It was always an uncomfortable time. We’d have to be dressed up, which meant not really being able to play or do anything fun, not that there was anything fun to do there anyway. The only saving grace was the TV set because Grandma could get all the New York City TV channels we could not. So we could at least watch old movies and programs like “The Thunderbirds. But there were strict rules in her living room, and God help you if you broke them.

For one, we couldn’t touch the TV. If we wanted to change the channel, we’d have to ask an adult to do it. If you were even in the vicinity of the TV set and she walked in, she would start yelling. The living room itself was equally uncomfortable, with plastic runners across the rug and plastic sheets on the couches so we couldn’t mess anything up. Also, forget about bringing a snack in there or touching the candy in the dish on the end table. And don’t touch any of the hundreds of her knick-knacks scattered around the room. One time, one of us accidentally broke one of her statues, and Dad actually hid it so we wouldn’t get in trouble.

But on that morning, all of that fun would come later. For right now, we were marched outside to say hello to Dad’s grandfather — my Grandmother’s father — who was usually referred to as “Little Grandpa,” because he was shorter than Dad’s father, who was “Big Grandpa.” Little Grandpa was very old at that point, and mostly stayed out on the patio in good weather, or upstairs in his room in bad weather, as he and Big Grandpa did not get along much.

On this particular Spring Sunday morning, he was sitting outside. So, we dutifully went up and said hello and stood there lined up like robots in front of him as Dad talked with him. Little Grandpa didn’t say much that we could understand. He had no teeth, didn’t speak much English, and just kind of sat there nodding his head at us. But there was one thing he would always say, every time we saw him. He would shake his head, point a finger at us, and look at us very seriously, as if he were about to deliver a sage bit of wisdom that would save our lives. He would draw himself up, raise his voice, which was very raspy, and say in a Slavic accent, emphasizing each word slowly:

“You…lucky…you…got…Richie!” Richie was my father’s nickname.

He would then shake his head again, fold his hands, and look down at the ground, I guess satisfied that he had told us this.

I was never sure what to make of it. Did I really trust a toothless old man who spent most of his time drunk? And given Dad’s alternating good and bad moods, I wondered why we were so lucky. But being a kid, I remember thinking, Well, he is an old man, and an adult, so he must know something. He must be right. I also wondered, if we were so lucky to have Dad, how bad were his brothers to live with?

So we just smiled and agreed, “We lucky we got Richie.”

But to this day, I’ll be damned if I know why…or if it was true.

Of my two parents, there is no question that Dad was the interesting one. And I mean that in a kind and grateful way. Whatever else I will say about him in this book, like all human beings, even ones who do horrible things, he also did good things. No one is *just* evil. And maybe it’s because of those things that it was so hard to know what to make of him, or to even know I should stand up to him.

He was passionate, could be charismatic, funny, and he knew so much about so many things — aircraft engines, metallurgy, rocks, and minerals. He worked in the Experimental-Test lab at Pratt & Whitney, a jet engine manufacturer in East Hartford. This was during the early years of the 1960s Space Race, an exciting time of science discovery when everything seemed possible. Those were the days of watching Mercury rocket liftoffs on TV in the morning before we left for school. And that was something especially relevant to us since Dad’s company was heavily involved in making components for those rockets.

He had so many interests, tried to get us involved in them, and educate us about the world around us. He would bring home chunks of metal to show us what these things were. I was particularly entranced by titanium. It was something new, he explained, important for planes, engines, and spacecraft, and revolutionary because of its amazing strength as well as being lightweight. To this day, I have a fondness for the metal. I gifted my husband a titanium crowbar one Christmas, I wear titanium-wired earrings because of my metal allergy, and my husband reset my engagement diamond into a titanium wedding band.

So, Dad was all about “doing and learning,” and he took great pains to instill that in us. He assigned us books to read during the summers, and even wrote up “tests” for us to complete, with questions like state capitals, math problems, grammar tests, and even Morse code translations. And he wrote these by hand, one for each of us. There were no PCs or laptops then.

That mantra of his, “Don’t grow up to be a stupid woman. Go to school and become something,” was a constant refrain, drilled in thousands of times, in front of my mother, who never went on to a formal career. These days, I see how harmful that mantra was, and how it represented so many undercurrents in our lives as well as in their relationship. But that is only now. For all our lives, then, the message was clear — sitting around and just “playing” wasn’t good enough. And just because it was the 1960s and women weren’t supposed to “be” anything and couldn’t yet even get a credit card in their name, that didn’t matter. He would make sure we “did things” in life, and even at home, we all knew that when he was around, we’d better be busy doing “something.”

Yet I will give credit where credit is due. His ambition and achievements were impressive in view of his background. Growing up in a rough end of Bridgeport, CT, he often got into fights, skipped school, and would get caught by truant officers. After an English teacher told him one day to come back for extra help after school or don’t come back at all, he quit high school at 16.

But after a couple of years of setting up pins in bowling alleys and working department stores, he joined the Navy — and LOVED it. It saved him. For the rest of his life, he would talk about the Navy and what it did for him personally, over and above all the traveling it enabled him to do. I often wondered if he made a mistake getting out after 4 years. But either way, no question in my mind — he would have had a lifetime career in and out of jail if it hadn’t been for the Navy. They took his rage, disciplined it, and channelled it into positive things.

I remember him saying how one time, as a punishment for Dad’s attitude, a Navy chief on his destroyer gave Dad a toothbrush and made him clean the entire mess hall on his hands and knees to burn out that anger. Dad talked about getting into fights on shore, landing in the brig, and being mocked by Marine guards. He was an angry young man carrying a huge wound inside.

In one way, what saved him then was himself. He managed to get transferred into the ship’s radio room, and that turned him around. He had earned his ham radio license on his own during his teens. Despite his performance in school, he got interested in the new science of radio in the 1940s and taught himself Morse code.

He drilled himself on the dots and dashes that represented each letter of the alphabet, and learned to tap out words on a Morse code key, struggling to get faster. He would listen to the almost unintelligible dit-dah sounds that crackled over the receiver and translate them back into words. Even though he would get stuck, get the words wrong, and be too slow, he was relentless. Finally, at age 19, he earned his official Federal Communications Commission General Amateur Radio License — the one, as he pointed out, that was an unrestricted Morse code license. He didn’t want the one that used voice communications. He wanted the badass one, in his view. Anyone could talk on a microphone. Not everyone could master Morse code transmissions.

What was even more of an achievement is that he pursued that through his teens, while living in a rough neighborhood, with little money. I remembered him sharing how he spent hours with his grandfather, standing in lines for bread, milk, and cheese during the Great Depression because there was not enough food. Yet, he accomplished this success with no help or encouragement, living in a crowded house with many siblings, an alcoholic father and grandfather, and an abusive mother. He did it himself, as he would do so many things in life.

I have to hand it to him; he had passion, determination, and ambition, and he wasn’t afraid to work hard. After he married, he left the Navy and worked in the factory at Pratt & Whitney. He wasn’t able to break into the small-town factories in Torrington, so he drove almost an hour each way, every day to work there. It was a source of pride to him to say he did that and gloat that it was a much bigger world with more opportunities.

By the time my parents had two of us, he wanted to move up out of the factory, so he put himself through what was then Ward Technical School, attending full-time, while working full-time, and sleeping in the car in between both. Somehow, he managed to make it through the 2-year program, and one of his instructors, who didn’t think he would make it, actually shook his hand on the graduation stage. That was a story Dad told us often, another source of pride, especially that he did it the hard and fast way. It was a family ethic that if there was an easy, gentle way to do something, or a hard and faster way, you did the latter. No wasting time, being patient and gently-paced. He showed the world that he not only worked hard, but did it the HARDEST WAY and STILL succeeded.

He would also talk with pride of how in 1960, he survived a lengthy work strike and his boss actually held his job for him. I vaguely remember that time — it wasn’t fun having him around all the time, especially with only a small amount of money coming in from the Union, but at least he spent some of his time helping my Grandfather paint the house that summer, and then would take his turns walking the picket lines.

Between uncertainty about how long this would go on, not much money coming in, and most of all, the question of whether he would have a job after this was over, for sure it was a stressful time. But he always retold the story with pride, of finally returning to work and learning that his real tough-guy General Foreman, who was a never-ending source of stress for him, came up to him and said, “I’m glad you’re back. I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to hold onto your job for you much longer.”

Apparently, a number of the “scabs,” as he called the people who would cross the picket lines and do the jobs the striking employees walked out on, tried to apply for Dad’s job. While Dad’s boss could cause Dad a lot of stress, his boss apparently also managed to scare off the “interlopers” by telling them what he demanded and then asking if they really thought they could do the job as good as Dick. So yes, Dad loved that story, too.

At home, his office had charts on the walls with cross-sections of aircraft engines, including the then-new JT9D that went in the Boeing 747. There were models of PT boats and his old Navy destroyer — the USS Stoddard (DD 566) — and books. All kinds of books — UFOs, politics, war history, biographies. And my Mother’s old nursing books.

She had at one point thought about being a nurse, like her cousin, but for whatever reason, quit nursing school. She had also considered being a nun, like her older sister, but gave up on that, too. As many times as I asked her, I could never get her to say why she quit either one. She wouldn’t speak. I always longed to hear what was in her heart, but as with so many things about her in life, she would remain an enigma.

But Dad? He was always pushing himself…and us…to keep growing. One summer, he made us learn to write business letters and then write to the Departments of Agriculture in many states to ask for soil samples so we could learn that the geology and science of each place was different. Some states actually answered us and sent samples, which he took and layered in tall, narrow jars labeled with the names of the state that sent the sample. I still have those jars, and I have to admit it *was* cool to see the regional differences. Dirt is not just dirt.

In his job, he was a foreman for over 50 men in the lab, so he had to learn how to understand and manage them, and to write reports. The company would often send him for various manager training sessions, which he would then give to us after our Sunday noon meal.

One Sunday, he went on for an hour about “Human Relations” — a seminar he had to attend on how to effectively understand and interact with people. I consider this a bit of irony, given his domineering rule over our house. But I suspect it fed his knowledge of how to read people, determine what they needed, and then use that to effectively manipulate them. All I know is that he LOVED that course.

Another time, it was a passionate dissertation on this amazing book from his manager’s writing class: Strunk & White’s The Elements of Style. Again, an ironic twist in that the man who quit high school because he was failing his English class later was practically a prophet for the blessings of this book. Nothing against the book — it is an absolute classic and still in print today…for good reason. But my 9-year-old self just wanted to go out and play, and my adult self avoided it just because of its association with him. Yet, it stuck with me because it was another one of his lessons to remember for how to succeed in a man’s world.

He took us on day trips to so many places — partly to learn, though I expect these were all things he wanted to visit because they were his interests. I don’t know if he ever considered a place my Mother might have liked, as I know she was not thrilled with these, but she never said anything. I also have no idea if she even had an idea of where she wanted to go.

One time, he took us to the Hartford Public Library — which was amazing to me because it was so much bigger than the library in our town and had things like microfiche readers and little rooms where you could listen to all kinds of music with headphones. Another time, we toured the homes in West Hartford of authors Harriet Beecher Stowe and Mark Twain. I especially loved Twain’s home because it was built in the shape of one of those Mississippi riverboats he used to work on in his youth, and he had a sign inside the front door telling any would-be robbers where to find all the silver and valuables so they wouldn’t wake anyone sleeping upstairs. Twain’s office upstairs had a pool table that he used when stuck in his writing, and a brand-new technology for his day — a typewriter.

Visiting the house also made Twain real to me as a person. I’d already read his books, Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, even though we hadn’t gotten to those yet in school. But one day, while playing upstairs in my grandparents’ apartment, which usually involved exploring their cabinets, drawers, and closets, I came across old copies of both left behind by one of my uncles. Intrigued, I curled up in a corner and just consumed them both.

Another time, it was JFK airport in New York City, so we could see people from all over the world coming into the terminal and be aware that planes could take you anywhere. This was back in the day when you could enter the terminals and mix with passengers, and when the Boeing 707 jet was a revolutionary new technology. I still love airports and live 10 minutes from one now.

We spent one vacation day of his driving to the middle of the state and down a dirt road to an abandoned quarry that was now a pit that “rockhounds” — amateur geologists — could pay a small fee and climb all over looking for rocks and minerals. My Mother sat in the car, angry, but I loved it. We had quite a rock collection, and I learned early to identify the differences between slate and mica, garnets and quartz. There were also lessons on fossils, though to this day I am not impressed by dinosaurs and those show-off T. rexes. I have always been drawn to the unusual, the small and overlooked, the things living in the background. My two favorites are small sea creatures — one called a brachiopod, and the other, a trilobite, an ancient relative of the modern pillbug.

One of my prized possessions then was a blue-rubber-handled, metal, rock chisel that I picked up at a museum gift shop one time, minus the hammer. That would have been dangerous at my age — a good way to lose an eye. But even though I couldn’t really use the chisel, I just loved to have it and hold it. Over the years, I lost it, but more recently found myself a new one, AND that rock hammer as well.

Another day, I got to visit the back work area of the Copaco grocery store. One of Dad’s Pratt & Whitney co-workers also worked part-time in the meat-packing area of Copaco’s, so he gave us a tour. As we walked along a metal catwalk above the open back area, I saw the rabbi and a butcher working on a recently slaughtered cow that was hanging upside down by a chain, its blood draining out. It was both scary and fascinating, especially watching the rabbi perform his ritual. It seemed very holy and magical and was my first introduction to Judaism, something I would become very acquainted with years later.

And there were museums — so many of them. Aquariums, planetariums. Marconi’s telegraph site on Cape Cod. The USS Massachusetts World War II battleship in Fall River, MA. The submarine base in Groton, CT. And two favorite museums in Hartford — the Wadsworth Antheneum art museum, my first trip ever to an art museum, and the Children’s Science Museum in Hartford. That latter one stays with me to this day since I expected the police would come that night and arrest me.

We were wandering one of its darkened exhibit rooms there, this particular one filled with animal skeletons and skulls. Everyone else had moved on, but I stayed behind, drawn to this walrus skull in the middle. It was like an altar, glowing in the light of a small lamp in the middle of the darkened room. It just called to me.

Quietly, ever so carefully, I approached, fascinated by those two long, white, smooth tusks. I just couldn’t help myself as I was overcome with curiosity about what they felt like. I looked around — no one was there. So I very gently reached out with just one finger and barely made contact with one tusk. In a flash, it slipped out of the skull’s socket, crashed to the floor, and smashed into many pieces. It had apparently been hanging in place by just a single plastic peg, and when I touched it, it let go.

Horrified, I ducked behind an exhibit, waiting to be discovered and hauled away. When, after a few minutes, no one came, I ducked out. It was only later that night that I confessed to my parents, because I expected to be tracked down by the police, and figured my parents should know. To my amazement, they just calmed me down and were not upset. I think that was one of those things about him — he respected that I wanted to learn and thus reassured me no one would ever know. So, to the Children’s Museum of Hartford, some 60+ years later, I am sorry about the walrus tusk. I didn’t mean to break it.

There were, of course, simple Sunday drives, visits to amusement parks, and beaches. And longer vacations — camping in Vermont, and Lake George, NY; trips to Canada and Niagara Falls; tours of the Ford plant and Greenfield Village in Detroit; and my most favorite – Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, a town-sized living history museum set in the Revolutionary War era. To this day, I still return there, and I loved the place so much that I actually wrote a book about my 50 years of visits to the place.

There were others, including the horse-race track at Saratoga, NY, Cape Cod, and marine research labs. And strange as it sounds, to this day I love the sour smell of salt marshes — the nurseries of the ocean — and climbing all over snail-covered boulders and tide pools in Newport, Rhode Island.

As much as I loved all the places he took us to, one of the most memorable ones for me was Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park Laboratory in Orange, NJ, which was by then a museum. One Saturday morning, he just got up and announced we were driving 3 hours to tour this place. Again, I am not sure what my Mother felt — in all of these things, she was almost like a non-person, expressing no choice or opinion, except for sometimes having a sour look on her face. But I loved the place. It was an early 1900s chemistry laboratory with huge rooms filled with solid wood tables, jars of chemicals, experiments, and old log books. I daydreamed about what it would be like to work there, mixing yellow sulfur powder with other chemicals in fancy blown-glass flasks.

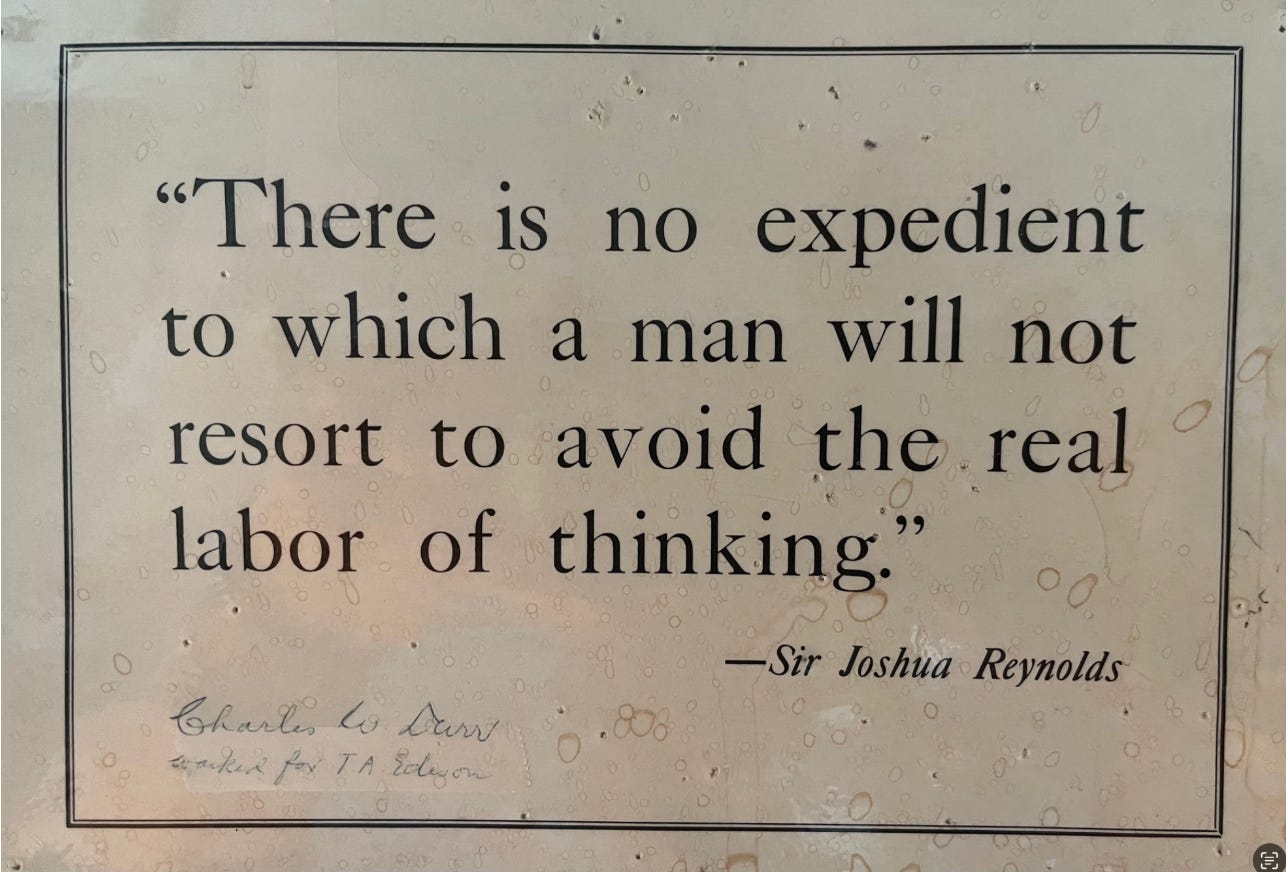

But the most incredible thing of all was a man we met there, an older gent who was one of the tour guides — Charles W. Durr. He had actually worked for Thomas Edison! I was blown away. Here was an actual living, breathing person who saw and talked to Thomas Edison! In my mind, Charles W. Durr was better than a rock star.

He shared several stories from “those days,” and then pointed to a framed sign, copies of which were hung all over the buildings at Edison’s insistence — a way to communicate Edison’s work ethic to his employees. It was a simple sign, with a quote by someone named Sir Joshua Reynolds. While I didn’t know who he was, the quote intrigued me, and I ended up buying a copy of it from the gift shop — I ALWAYS bought something from science museum gift shops. Or picked up a piece of coal or rock, or something from these places as my souvenir. But after buying the sign, I went back and had Mr Durr autograph mine: “Charles W. Durr, Worked for TA Edison.” That sign still hangs on my wall. And these days I also pay close attention to its meaning:

As we got into our teens, we learned to manage a vegetable garden, raise chickens, make maple syrup from trees he tapped on his land, and perform car maintenance. Dad insisted that we learn how to change the car’s oil and tires, and help with brake jobs and tune-ups. I admire and appreciate his foresight on all of that, especially given that this was unusual in the ‘60s and ‘70s for a dad to teach his daughters about cars. I will also say that I am now grateful for fuel injection, the fact that cars no longer have carburetors, points, or distributor caps, and that I will never need to see a timing light ever again…or get yelled at for holding the flashlight wrong.

But whether I loved or hated anything he chose to teach us, I am deeply grateful that he did all of these things. All of it gave a richness to the good parts of our childhood and really formed who I was. On some level, all of these things fed my own natural curiosity about the world, and my daydreams of what I could become in life.

As to his motives, I don’t know whether he actually saw something in me and was genuinely trying to foster it, or if I was just an “extension of him and all his unfulfilled dreams.” I know he wanted his kids to be something, he loved the sciences, and mocked my wishes to be an English teacher or writer. As the oldest child in our family, like he was in his, he identified with me and projected all his unfulfilled ambitions onto me. And especially since his firstborn, a son, was stillborn, I became the de-facto “standard bearer” for those.

In one respect, maybe it is good my brother didn’t live. My father’s powerful ambitions were hard enough on me at times, and he commented that he gave me a break because I was a girl. I can’t begin to imagine how much harder he would have been on a son, and how destructive that could have been for that son…and me if that son turned abusive in response.

Whatever his motives — part goodness, part selfish interests and ego, part hoping to show off his “smart kids” — who knows, and it doesn’t matter. What did matter is what I did with it all, without even realizing it.

Everything he taught, I absorbed like a sponge. Even as I might prefer playing with my toys, on some innate level, I also sensed that he was handing me something I would need someday. If I wanted to reach my dream of being a scientist or a marine biologist or a writer or whatever, if I wanted to live and work and succeed in the world of careers…of men… I would need the things he was sharing.

On another level that neither of us was aware of then, he was feeding me the very knowledge I needed to survive him, deflect his assaults, and grow despite his efforts to control me. I took in his stories of his early life and struggles, sensing both his hunger for knowledge and all that wasn’t possible in his childhood, as well as his unstoppable determination to get whatever he set his sights on. I always felt very proud of him that he was a person able to take on anything, no matter how hard, and the harder the better sometimes, and through sheer force of will and hard work, achieve his goal. If he really wanted it, he wouldn’t let anything stop him — which would later be an infuriating disappointment when I had to stand up to him and hold him in check because he wouldn’t get the help I begged him to get. But none of his lessons were lost on me, whether I knew it consciously or not.

The reality is, once you give the talisman of knowledge, and more importantly, feed that person’s LOVE of acquiring even more knowledge, you will NEVER be able to control that person forever. It might take them years, but they will learn to question and push and demand truth. And sooner or later, they will grow past your ability to contain them, snapping the constricting bonds through sheer force of their own will to break free.

A seed planted, even one that takes years to sprout, WILL eventually burst through hostile earth into the sunlight if it’s given the right conditions. For me, the right conditions were the experiences and knowledge he gave, along with the realization of all the unending possibilities “out there.” That “fertilizer,” mixed with my own nature of dreams, unquenchable curiosity, and my own hunger to understand deep things in life, would eventually be the formula that saved me — the “ore” of his knowledge and my own raw materials fired together white-hot in the crucible of pain and abuse. I’d be changed in a way that would help me ultimately transcend him and the things he did to me. I just wouldn’t know that power was there for a very long time. I was like Dorothy in the old Wizard of Oz movie, never knowing I had the magic shoes that could take me home…or that I had the right to use them.

As with so many things in that house, which were a toxic stew of confusing messages, gaslighting, and abuse interspersed with “love,” it was just impossible to understand for so long what was really happening. More than one therapist told me that if he had been all bad, it would have been easy to break away and never look back. But in a house where abuse and love are insidiously mixed and delivered in a very calculated way to maintain control, it can be almost impossible to see the truth and get free. So it would take a very long time for my seed to sprout.

Until then, I just went moment-to-moment, assuming this was life, and….I was lucky I got Richie. I deflected his assaults as best as I could with whatever means I could bring to bear. I survived the abuses I couldn’t escape, ducked and dodged whatever ones I could, learned in the good moments, and fed my soul with the wonders of that world “out there,” in the bad. I absorbed his work ethic and the skills he acquired to build his career. And took in his mantras for life: 1) Never give up. 2) Always go for the hardest, most difficult challenge, AND succeed. 3) Don’t grow up to be a stupid woman. Be something.

All of this got me out eventually, and left me with a lot of “emotional cleanup” now, especially for rule number 3. His indoctrination, and my mother’s passivity, would drive a mantra of my own through most of my adulthood, one I am dismantling and rewriting only now…..”Never grow up to be my Mother.” That would form the basis of a huge wound of its own.

Leave a comment