The early scientist:

The last of the cartoons had just finished on TV for that afternoon. As I walked away, I was still laughing at the character who had accidentally swallowed a bar of soap. Immediately, bubbles foamed up and out of his mouth, and his hiccups generated more soap bubbles. And that’s when the question popped up in my young brain:

Did people *really* cough up soap bubbles if they swallowed a bar of soap?

I thought about it and then headed for the bathroom. There was only one way to find out, and my scientist mind knew just what to do. Marching up to the sink, I picked up the bar of soap and shoved it in my mouth.

Photo by author

Horrid sensations, I can’t call them “flavors,” flooded through my mouth, and I immediately spit the bar into the sink. Coughing and choking, I grabbed a glass and started rinsing my mouth with water while I tried not to vomit.

Hearing the chaos, my mother came into the bathroom to see what was wrong. In between spitting, choking, and heaving, I told her what I’d tried.

My mother’s face was a mixture of shock, disbelief, concern, and finally, amusement.

“Why did you do that?!” she said, laughing. *I* don’t even make you wash your mouth out with soap!!”

Why, indeed? Because scientists find out by doing.

Not long after that incident, and still not having learned my lesson about when to do things and when not to, I was playing with my yellow plastic cowboy pistol. No doubt we’d been having a day of cowboy battles in the house.

Afterward, I examined the gun more closely. I loved that pistol because it came with yellow plastic bullets that meant you could actually shoot at things. Yes, again, it was the 1960s.

Looking down inside the barrel, the question formed in my mind:

“What do the bullets look like when they come down the barrel?” And immediately, I had an idea for how to find out.

The gun barrel had a little lever on the end of it that served as a “safety” mechanism. If you didn’t want the bullets to come out, you just flipped that lever down. So there was my answer – plain and easy. Just put on the safety, then watch the bullet come down the barrel.

I loaded a plastic bullet into the cylinder, raised it up to my eye, looked down the barrel, and pulled the trigger. There was only one problem. In my haste, I forgot to flip the lever down.

The bullet hit my eye with a piercing force, and pain seared through it. I screamed and started crying. Mom came running.

“What’s wrong?!” she asked as she lifted me up onto her bed to see why I was clutching my eye.

In between heaving sobs, I managed to blurt out, “I shot myself in the eye!”

She was momentarily speechless, no doubt taken aback by my thought process…or lack thereof. Then she shook her head and exclaimed, “WHY did you do that?!”

“I wanted to see what the bullet looked like coming down the barrel, but I forgot the safety!”

She sat there for a moment, her mouth open, shaking her head. Finally, she said the only thing, I guess she could think of, “But Roy Rogers wouldn’t have done that!” Roy Rogers and his wife, Dale Evans, had a western-themed TV show that we watched faithfully. And yes, he never would have done that.

Both of these incidents were not far removed in time from my experiment in the garage to prove that her glass vase was made of “hard glass” and so it would survive being thrown against the concrete floor. Or another incident where I learned the law of levers the hard way by climbing onto one end of an empty bench and standing on it. Immediately, the other end flipped up, I fell, and my end of the bench smacked me under the jaw, necessitating another trip to the ER for more stitches.

So I have to wonder how I ever ended up in science. While it was clear that I understood the concept of doing an experiment to learn, I had missed one important word in the scientific process: “Controlled” experiment.

As I got a little older, I learned how various things around the house worked. Washing machines, tools, Mom’s sewing machine. One time when she was out, it jammed up while my sibling was using it. I was certain I could fix it, so I proceeded to take apart the insides of the bobbin area.

Unlike my past experiences, I knew to be slower and to pay close attention to how each piece came out. I lined up the pieces in order on the table, managed to pull out the jammed-up thread, and replace the pieces correctly, all before she got home. The machine even ran much quieter after that. My science brain was evolving and improving!

Dangerous curiosity:

However, I shudder to think back to another day around the same age that could have ended much worse. It’s not a stretch for a child to go from plastic bullets and sewing machines to trying their expertise at any other things they find in the house.

My father always stored his .22 Remington rifle on the side of his bureau, secure in the knowledge, I guess, that if he told us to leave it alone, that would be enough. I also knew that he kept the bullets, the rifle clip, and also a small pistol in the top drawer of that bureau. While I never could find the bullets for the pistol to play with, everything for the rifle was right there. And I knew how to operate it and load it from the times he took me shooting.

My mom was on a quick errand, and Dad was at work. Filled with my certainty that I just needed to be slow and pay close attention, I decided to test myself to see if I could remember everything he taught me about loading, unloading, setting the safety, and pulling the trigger.

For the next 15 or 20 minutes, while the Universe no doubt held its breath, I practiced putting bullets into the rifle clip, putting the clip in the gun, and then popping it back out. Then, with no bullets in the gun, I practiced putting on the safety, holding the rifle, and aiming it. I may have even pulled the trigger since I knew I had taken the bullets out. But my God, as an adult, I know just how awful that could have been. I know now from my own target shooting experiences how important it is to always keep bullets out of a gun until ready to fire, and how vital it is to clear a gun because even when you think it’s empty, it might not be.

I am only grateful that my experiments with the rifle went better than the pistol. And I don’t think I ever did it again, probably since I was satisfied that I remembered how to operate it.

It goes without saying that my father was an idiot to think that just telling his kids not to touch his rifle would be enough. Kids’ brains aren’t ready for firearms. And all of that should have been locked up.

The MacGyver mind:

So, in view of all of this, there is no question I had that curious science mind. But I wasn’t the total scientist or engineer because I lacked that slow, analytical, SAFE approach to my experiments. Instead, I was a hybrid of the “creative, the visual artist, and the scientist, along with a heavy dose of a “Robinson Crusoe” approach to things.

In the book of the same name, Crusoe, stuck on a desert island with only whatever supplies he had from his stranding, had to use his mind, creativity, and hard work to survive. Over time, he not only endured but thrived. I have always loved that challenge of taking “whatever life gives you in the moment” and seeing what you can make of it.

There was a TV show many years back called “MacGyver.” The main character always saved the day and fought off evil, not with guns, but with his brain and the few items around him in the moment. In fact, the term became an entry in the Merriam-Webster dictionary for the transitive verb: “MacGyvered, MacGyvering, MacGyvers.” It’s all about improvising to fix, create, or form something using only what is on hand.

My husband noted one time that I always seem to approach life with an attitude of “make the best of things in the moment.” And I think that is true. I always moved through life “moment by moment,” figuring out how to survive or endure, using whatever was around me in that moment. And my most powerful tool, imperfect though its judgment was at that time, was my brain.

That “sponge brain” and hard questions:

To this day, I love to learn. I’ve always been an information sponge. Even at 4 or 5, when we drove the hour trip to Bridgeport to see my grandparents, through winding backroads and several towns, I knew the whole way. Every single turn.

And not only did I pay attention and absorb things, but I also thought about them and asked questions.

When I saw the trash in the Naugatuck River, and saw how the rubber factory used to dump this yellow-black liquid into the river with no treatment, I had questions like: Won’t there be a point where the water can’t “absorb” it all? Won’t it kill the fish? I kept wondering, but figured if the adults did it, they must know better. But still…it just seemed wrong.

Another time when I was very young, and gasoline was about 15-16 cents a gallon, I would watch the two spinning dials at the gas pump. The price dial went so slow, while the gallon dial spun fast. I asked an adult where the gas comes from. When they explained about the Middle-East oil wells, I asked, “What happens if they don’t want to sell it to us anymore?” They immediately pooh-poohed that question and said, “That will never happen.” And it didn’t, until it did….in 1973 with the Oil Embargo, and the long lines at the gas stations. Ironically, now it’s the price dial that flies by while the gallon dial goes ever so slowly.

Probably the most controversial discussion my questions got me into, though, was after the Sunday Mass, where the priest lambasted birth control. I got in the car and declared that I saw nothing wrong with Birth Control. I got lambasted next. But in my mind, I kept thinking — If God helped us discover it, why couldn’t we use it? Why should we have to have children if we don’t want to or can’t afford any more? But after that, I learned to be more careful about what questions I asked or what opinions I declared.

Toys:

Even all of our toys then were about doing, thinking, and learning.

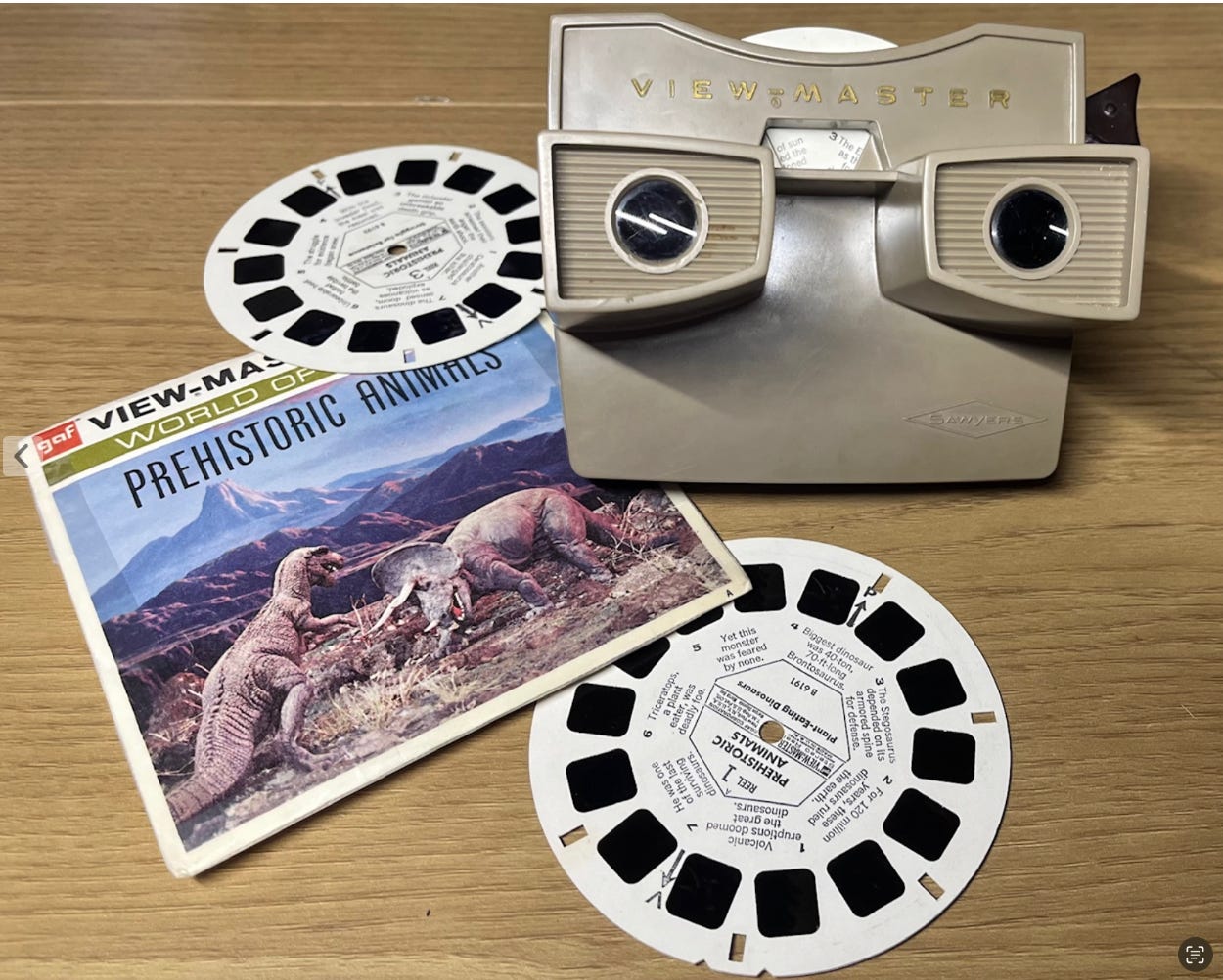

We had things like a View-Master, where you could flip the slide pictures and go anywhere in the world, or back in time. There were creative things like a Vac-U-Form “Thingmaker,” and printing presses, Lincoln Logs, the Kenner slideshow projector, and the car dashboard with a wheel and dials. Those things were all about “doing and creating.”

And I loved making models — poorly — but still. There were old cars, and ships, and one year I got the kits for the Visible Man and Visible Woman. They were clear body shells that came with internal organs you had to paint, assemble, and then determine how to put them inside the body. The Visible Woman even came with the “optional pregnancy insert,” complete with a larger abdomen plate and a fetus in the uterus. So at a very early age, I knew how the internals of the body were set up.

Even our games were about strategy, deduction, and information: Card games like Setback and 9/5 required strategy and teamwork. Checkers, and board games like Clue and Lie Detector, Mousetrap, Concentration, and later, Monopoly and Password all required thought.

And making a list of the toys we wanted for Christmas was a learning exercise. We had to go through the catalog, find what we wanted, then write a legible list indicating with which toy catalog – Sears or Penney’s — it was from, as well as what page, item name, description, and catalog number.

Science kits:

Probably the most effective toys, and a safer outlet for my curiosity, were the science kits and books I received or bought with my allowance.

The microscope set I still have, just because of how I loved it. It also came with a dissection kit. At that point, I could save my allowance, then walk downtown to the cigar and hobby shop and buy formaldehyde-preserved frogs, crayfish, and fish. Then I would sit on the back porch with my tools and microscope and examine everything as I cut them up.

Another time, it was Uncle Milton’s Ant Farm, which they still sell today. Watching the ants arrange their tunnels, chambers, and work was truly amazing. And I had graduated from reading and making regular maps to the wonders of topographic maps. Who knew that all those little circles inside each other on those maps could show you the heights of mountains, the steepness of a cliff, and the depth of a valley?

But my chemistry set was the ultimate food for my imagination as well as my curiosity.

It came with tubes and racks, litmus paper, chemicals, and a booklet of experiments you could do.

About the same time, Dad assigned me a summer reading project. He had this old 1890s book called Men of Achievement – Inventors. While my siblings got storybooks or fairy tales, I had to read about men like Goodyear inventing vulcanization, Eli Whitney and his cotton gin, and Elias Howe inventing the sewing machine. I hated the book.

But even worse, he told me I had to write a 10-page report on one of the scientists or inventors. One of the entries in the book was Thomas Edison. While I have mixed feelings now about Edison’s methods and tactics, I was intrigued by his lab experiments. So I wrote about him. Now, I was a kid, and my take was to find the absolute smallest notebook I could get away with and hand-write 10 pages in that book. He, in turn, later took my report to his secretary, who typed it up to show me I had only written two pages.

But despite that, I was hooked and dug out more books on Edison. There was one more, in particular, that told of how, in his childhood, Edison worked on a train selling newspapers that he wrote himself. He also had a chemistry lab in the caboose where he did experiments in between his work. At least until he set fire to the caboose and got booted off the train.

My imagination was fired, though! I wanted a laboratory of my own. The only questions were: Where to set it up, and what to experiment on?

In considering convenience, in spite of my fear, I decided the best place was our cellar.

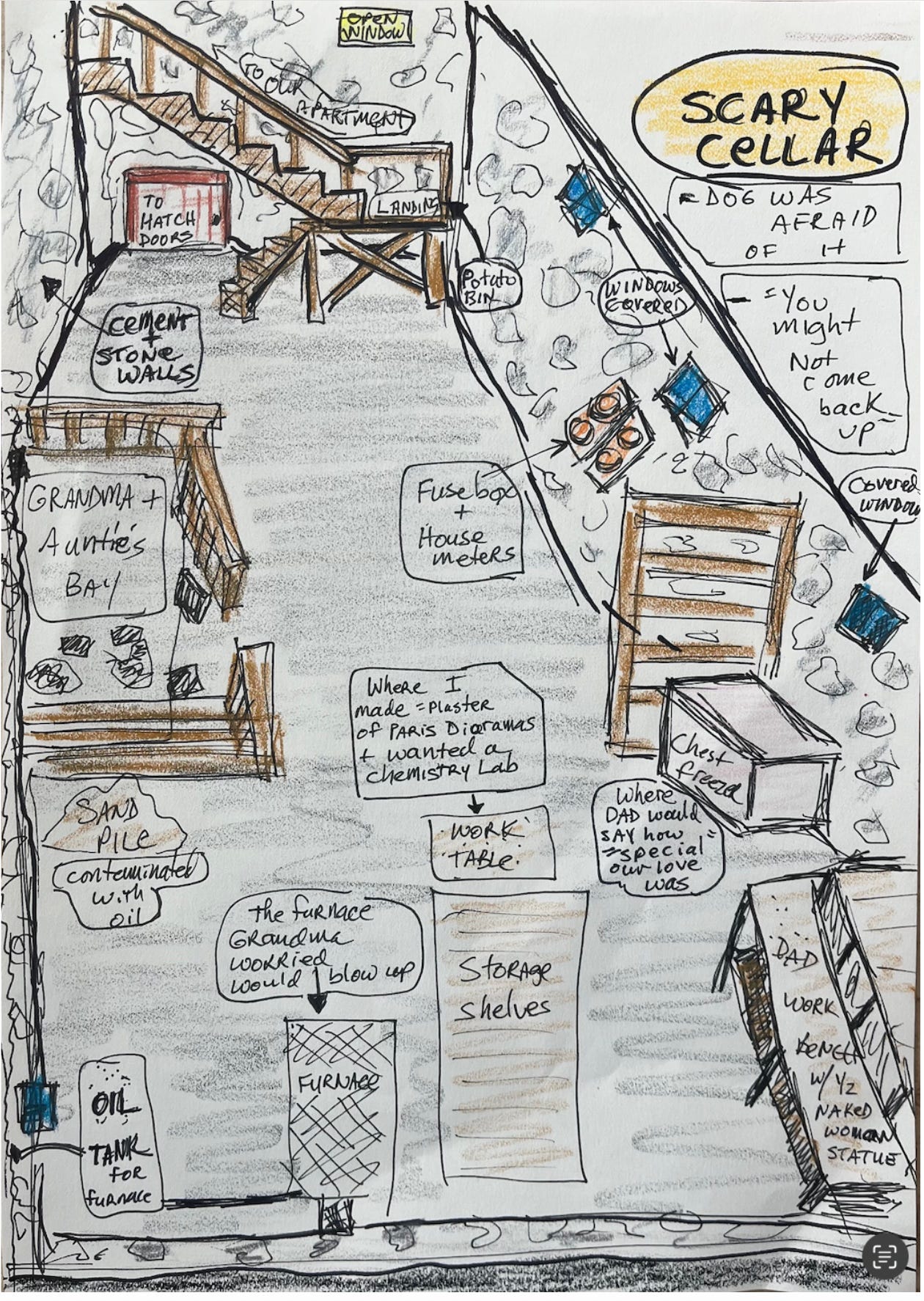

The cellar was a spooky place for a variety of reasons, including it being a place where Dad liked to molest me. But when he wasn’t around, well, it might be okay. You had to leave our apartment, go into the hallway, and unlock the cellar door to go down “into its bowels.” At least it felt that way.

It was an old space with concrete floors and rock-and-concrete walls. Some slatted wooden dividers enclosed the different storage areas on one side. Mom would often send us down there to get potatoes or meat.

I’d have to go down the rickety wooden stairs to where the potatoes were. Or to get the meat, I would have to continue down, then round the corner past the dark hatchway that led up to the outside. From there, if some ghost didn’t attack me, I’d have to walk past the spooky storage areas for the 2nd and 3rd-floor tenants on the right.

All of this was in the dark because our storage area and the food freezer we had were at the very end of the cellar. And that’s where the light switch was. I’d glance over my shoulder as I ran past the dim storage area, then bolt for the light switch. In the “safety” of the lit area, I could see better and verify no one was hiding anywhere.

On one side of our storage space was our food freezer, Dad’s workbench with the naked woman statue, and some storage shelves. To the right of those was the loud furnace, and then on the right wall, a large oil tank surrounded by sand we knew not to play in because it reeked of fuel oil. Once I was sure no one was there, I’d rush to get the meat or whatever out of the chest freezer, pull the light switch cord, and run full speed back upstairs.

A few years later, when we had a dog, we used to push the dog down the cellar stairs ahead of us and make her walk first across the dark cellar. But she would get part of the way there, then turn tail, run back upstairs, and abandon us to the dark. People say dogs are sensitive to the “paranormal.” I’ve often wondered if that cellar wasn’t haunted after all.

In any event, if I could stand the dark long enough to get to the light switch, and only go down there when Dad wasn’t home, it could work to have my lab there. So then there was the next question:

What would I create with my chemistry set? It had to be something amazing, like the things Edison did.

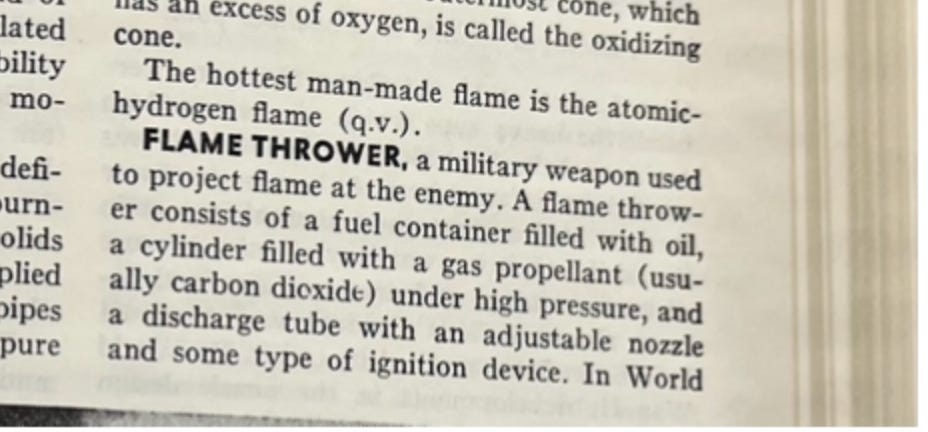

At the time, I liked to read encyclopedias and dictionaries. We had a 1955 edition of the Universal Standard Encyclopedias by Funk & Wagnalls. I was in awe, especially of the encyclopedias — SO much knowledge right at my fingertips, packed into each volume. So I flipped through one of the volumes, and my eyes landed on the picture of a soldier shooting flames out of a big gun. That was it! I would make flame-thrower gel!

But after exploring this more, I realized that I had no idea what went into flame-thrower gel. The things in my chemistry set weren’t going to do it. And the bottle of sulfuric acid on Dad’s shelf, I had enough sense by then not to touch.

Frustrated and stymied, I regrouped. In addition to chemistry, I also loved the ocean. In fact, I wanted to be an oceanographer when I grew up. I loved Jacques Cousteau’s book, *The Silent World*, and learned how he and a friend invented an aqualung. My father had also introduced me to the flyers from the U.S. Government Printing Office, which had a ton of things on the ocean. And one Saturday, we actually took a day trip to the University of Connecticut and walked the campus and saw biology labs. So yes, if I couldn’t create flame-thrower gel, I would do something with the ocean.

That’s when my inner artist kicked in. I had just finished reading a book — The Treasure of the Great Reef. It was the story of two boys who discovered a long-lost undersea shipwreck off the shore of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). They used SCUBA tanks and, in their many dives, discovered cannons and treasure. Given my “success” with Plaster of Paris and the Red Sea model, I decided I would create a model of the undersea wreck site they found. There was a map in the back of their book, listing where all the cannons and ship pieces were.

So while I didn’t end up as Edison the chemist, I did indulge my inner adventurer, artist, and oceanographer that summer, and lived for a while longer in my Moments of Respite.

With all of the qualities I’ve described in these entries, I worked hard to savor every bit of life I could, endure what I had to, and dream of a time in some distant future where the bad parts would be over. I would move on, it would be okay, and I would explore the world.

All of my Moments of Respite let me live “moment to moment,” and “MacGyver my life,” using what was in front of me. I would make the best of things as I could, until some time when it would all magically “be better.”

Now, for life “on Dad’s schedule.”

Leave a comment