Auntie Kitty and “The Boat”

Many of the things I know about my grandfather, I learned indirectly, from his sister, my great-aunt, who lived in the third-floor apartment of our house. She was “Auntie Kitty.” I have no idea of the origin of her nickname, but that is what we always called her.

When I was a bit older, I would bring her the Sunday newspaper, and she would make breakfast. Over tea, I could get her to talk about the early days of her and my grandfather’s lives, and she would share what they had been through. While she talked freely and answered my questions, Grandpa NEVER spoke of his early years or any of the struggles he had.

They were born in Connecticut. But their father was always off somewhere, and finally their mother got fed up and took the kids back to Slovakia with her. Ironically, they lived in a place called “Toporec,” which was only about three miles away from where my grandmother grew up. Auntie’s mother had family in Toporec, so it made sense that they went back there, I guess.

However, they weren’t there for too long when their mother died. I don’t know how the decision was made to ship her and my grandfather back to the U.S., but they were put on “the boat” and sent back. When they arrived at Ellis Island, they sent my aunt on to other family members, but sent my grandfather back to Slovakia, alone. Some question about a health issue. They should not have done that because both my grandfather and Auntie Kitty were U.S. citizens. Also, they were children traveling alone.

From what I gathered, the trauma continued. She bounced around with relatives, and she spoke about a lot of alcoholism in those households. So she lived a difficult life there. When she was old enough, she worked in factories in Torrington.

My grandfather, meanwhile, ended up staying in Slovakia until he was in his teens. That would also have been the time of World War I, and the Austro-Hungarian Army no doubt wanted to draft him. I found out from another relative that my grandfather managed to escape to Switzerland, then got a ticket on a ship to the U.S. While they almost didn’t let him back in, they said he had been away too long, relatives here in the U.S. vouched for him, and he finally got back here. As I said above, whatever transpired through all of this, he would never say a word.

I know from my aunt that when my grandmother had her breakdown, and also because of the money struggles during the Depression, she lived with my grandparents to help out. Eventually she married a widower with a young daughter. She had another daughter, and life was quiet for a bit. Then he died suddenly of pneumonia after a surgery. So she scrambled again, working in the factory while raising two daughters.

I know she worked very hard and both her daughters ended up married, with careers, and gave her grandchildren, whom she loved deeply. Also, as things eased for her, she indulged herself in nice clothes, always cooked herself full meals, and had a large group of women friends.

She was a fierce competitor and a very sore loser, especially in pinochle. God help anyone who had to be her partner, which was usually my grandfather. And if you made a wrong play in her mind, she would yell.

The other thing about Auntie Kitty is that she was probably better connected for any information than the CIA. If there was gossip, Auntie knew it, probably first. Not one of her better qualities in that regard. And for the years she had a “party-line phone,” which meant she had to share time on the phone line with other people; they must have been frustrated trying to get their turn.

She and my grandmother were always civil to each other, but where my aunt was hard and tough and always dressed up, my grandmother was an old country woman. And of course, Grandma had needed Auntie’s help during her breakdown. There were things just never discussed in front of us. Only bits and pieces of emotional undercurrents that I picked up.

I also know my mother had her issues with Auntie. Part of it stemmed, I think, from when my aunt lived with Mom’s family when my grandmother had her breakdown. My aunt was probably not the softest of people, emotionally. And later, when my mother lost her first baby, who was stillborn, my aunt had made a comment to someone that inferred my mother was somehow at fault for maybe waiting too long to go to the hospital. I only know Mom never quite forgave my aunt for that, and I can understand.

My grandparents’ marriage

Whatever their later years together were like, their wedding picture shows the hopeful joy of youth. They were wed in January 1926, and by the end of the year, they would have their first child, a daughter they named Mary. And as I noted in my grandmother’s essay, within 5 years, they would have 4 children, and the Depression would be raging.

As far back as I can remember, my grandparents always slept in separate rooms. I don’t know when that came about. Or why. Back then, it never occurred to me that old people might still like to sleep together. Being their age now, I know better.

She shrugged it off as her arthritis making her uncomfortable. Maybe. Maybe it was the years of struggle and stress. The fights over his drinking. Her emotional breakdown. Or both. Maybe it was that after 4 children in 5 years, with no birth control and a religion that forbade it, the only option to have no more was to stop having sex. Maybe that caused the drinking. But while they slept in separate rooms, they stayed together for life. Was it because they had to? Because that’s what they believed? Because, in spite of all, they did love each other? Who knows.

I only know that life can wear you down, and I am glad I grew up in a later generation. Whatever my own struggles, when it came to how many children I felt I could raise in a healthy manner, I had a choice. She did not.

Grandpa’s finger

Grandpa was a man who did a lot of hard, manual labor. And one of the ways I knew this was the can of Boraxo soap on their bathroom sink. Boraxo was a gritty soap that worked well on hands stained by the grime of working in factories. I knew of the soap from the commercials on TV that talked about borax and their 20-Mule-Teams. But my grandparents actually had some upstairs!

I would go in there to wash my hands just to play with that soap. The container was metal and had a lid you had to slide back to open and shake out the soap. And the soap was unlike anything we had. It was like sand. I would dump some in my hands and spend several minutes just rubbing the gritty pieces over my knuckles and in between my fingers, reveling in how it felt. I imagine they had to buy a lot more Boraxo once I discovered it in their bathroom.

The other way I knew of his work was his finger. From a young age, I knew that he was always missing part of his left index finger. I remember it being a short stub with a rounded end. When we asked about it, we learned it had been a factory accident. He worked for decades in the town’s brass mill. I don’t know his exact function, but it was hard, dangerous work. They made brass for many uses, but especially in the 1940s, brass for military ammunition. They were busy. The hours were long. And somewhere in there, he lost part of a finger.

In early 1958, my grandfather bought the house that I spent most of my childhood in. And that house was Grandpa’s delight. After such a hard start in life, after working so hard in a factory all of his life, and after having to rent from someone for so many years because he couldn’t afford to buy a house, imagine the joy of that man to finally BUY a house of his own! And he made it a family house. The family castle, so to speak.

While his older daughter, Sister Luke, and his son, the priest, were cared for by their respective orders, and his other son already had a house, this now took care of the rest of us. My family, he and my grandmother, and his widowed sister, all under one roof.

We had a safe yard to play in, with a sandbox and a swing set. He and my grandmother would sit on their front or back porches and just watch the world go by, and Grandma had her bed of peonies.

My great-aunt had a large space for all of her nice furniture, as well as a snuggly den and kitchen. And outside, she had a small patch of what I now know was chives. At that time, we only knew it by a Slovak word that sounded like “parunka,” though in researching it more, it was probably the word “pazitka.” Again, given the Slovak names for things, they always seemed exotic to me. Whatever they were called, I would often snitch a couple of blades to chew on when playing.

And Grandpa would spend his days fixing things, painting the house, or mowing the grass faithfully. When it snowed, he was out there shoveling, and eventually bought a snowblower that became his prized toy. The bottom line was that this was the family enclave where the entire family could gather, and that allowed everyone to have a bit of space to do what they wanted. He was content.

A man of many sides

Grandpa was mostly quiet. But he could enjoy a good laugh. He had dentures. Something we didn’t understand as kids. He would sit there and pull out his teeth, then challenge us to do the same. We would pull and pull, frustrated by our inability to match him. And now and then, he would let us have a sip of his beer — always Schaeffer — and laugh when we would wrinkle up our faces in disgust at its taste.

He was a man who had his values and opinions. After the 1955 flood ravaged our town, he was there, working hard to clean up the mess. He was a lifelong Democrat, always worked in City Hall at the voting lines for elections, and didn’t think man should go to the moon. He and my grandmother fought in Slovak, and he didn’t like her going to the race track. But they would sit there at night, side by side, watching the news and talking quietly.

I used to love to go through his bureau drawer when I was up there. Bits of who he was. A black set of rosary beads. A Slovak prayer book. A razor. For all the different aspects of him, there in that drawer was yet another one. In spite of all the Sundays he would spend at the club, he would also, each Sunday morning, dress in his suit,and go to church. I am not sure what it says…just that he was a man with so many facets to him. An enigma, keeping his own counsel.

Pretty Boy

Our parakeet, Pretty Boy, somehow ended up living upstairs with Grandpa. I don’t know how it came about. Certainly, it was the best thing for the bird’s nerves because it just kept freaking out as long as my Dad was around.

In thinking about it now, I have to wonder exactly what was said between my Mother and her Dad to have him take the bird in, especially since my grandmother didn’t like the bird and didn’t want it there. Was Dad going to kill the bird if Mom didn’t get Grandpa to take it?

I have always wondered if Mom ever told him what was going on in our house. Did Grandpa ask? My mother made it clear we were NEVER to say a word to her parents about how my father hit us. Was that embarrassment? Fear of my father’s retribution if she did? Both?

Regarding Pretty Boy, she had to have said something that convinced my grandfather to take the bird. But, however it came about, Pretty Boy moved upstairs. Grandma wasn’t happy, but Grandpa said, “Yes,” and that was that. And just as our dog, later on, would love my grandfather, Pretty Boy did too.

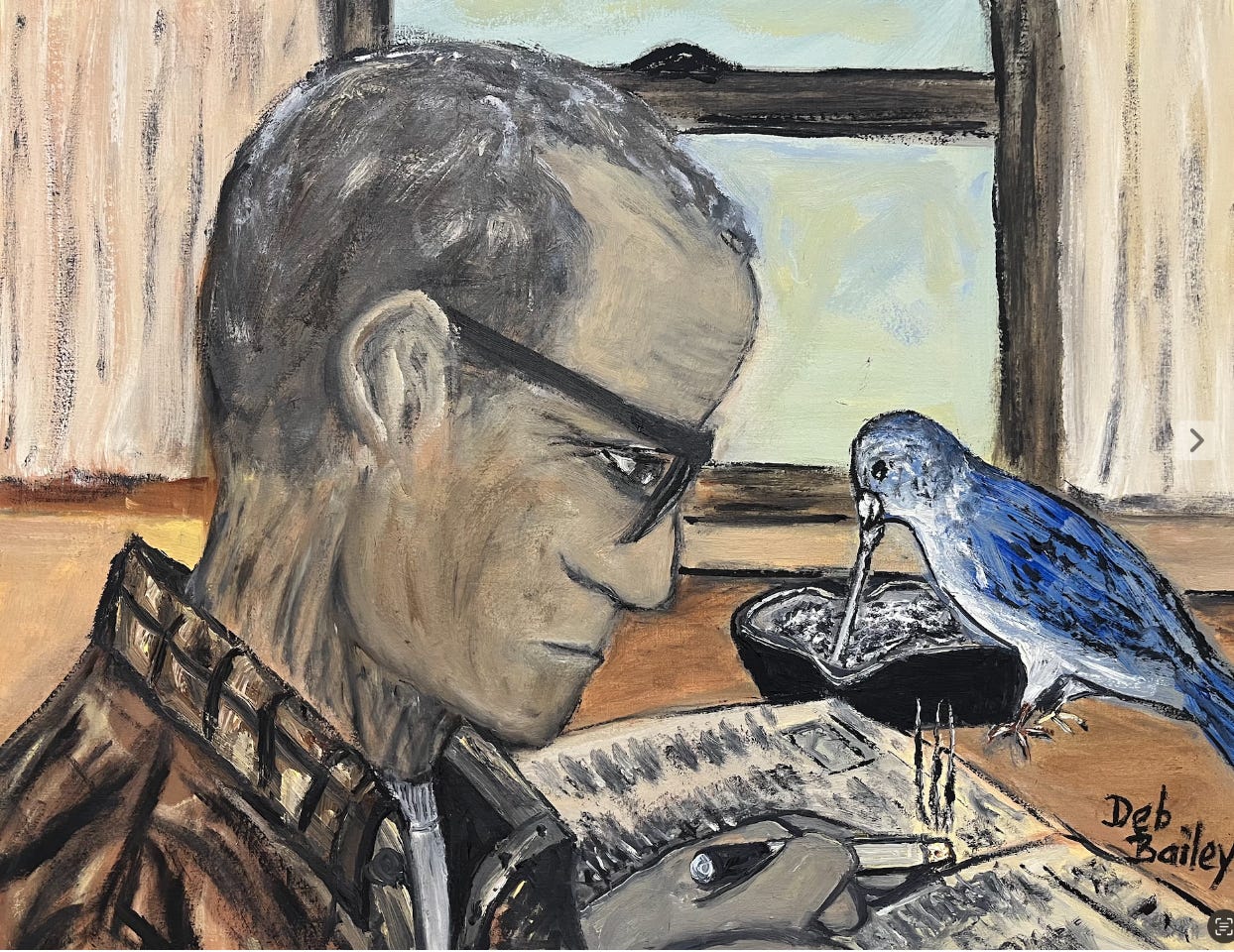

They had a morning routine. My grandfather would get up, sit at the kitchen table after breakfast, and read the paper while smoking his cigarette. Much to my grandmother’s frustration, Grandpa would let Pretty Boy out of his cage. The bird would fly around the house, then join my grandfather at the table. While Grandpa smoked and read the paper, Pretty Boy would perch on the ashtray next to him and nibble on the burnt ends of Grandpa’s matches.

Pretty Boy lived a very long, peaceful rest of his life upstairs and finally died a few months after my grandfather did.

The Club

I remember one Sunday when my grandmother came downstairs and was upset. It was that typical Sunday afternoon thing where it was getting late and my grandfather wasn’t back from the Sokol’s club yet. That was never a good sign and meant he was, no doubt, drunk. And she was upset, both that he would be drunk and would be walking home that way. So she came downstairs to beg my Mom to send my Dad to go and get him.

Dad, having had to do this as a kid with his own father, hated that job. And my mother hated those afternoons, too. She mentioned remembering when she was a kid, how her parents would fight every Sunday afternoon. Her mom would be yelling from their upstairs apartment porch down to him, standing below, drunk, and yelling back. I did not grow up around an alcoholic and never realized then how much that traumatized both of my parents. They barely drank in their own lives.

The closest I can come to understanding that experience is from a nightmare I had about a year ago. In the dream, I was living in a decent home, which was generally happy…except when the dad in the dream came home drunk. It was terrifying because everything was unpredictable. As the child in the dream, it filled me with this overwhelming sense of helplessness because when the person was drunk, they were not in control. They became someone else, someone foreign and frightening, and you couldn’t reach that “normal” person. In that moment, all you had was this other, mean person, and who knows what they might do. In the dream, I felt so alone and vulnerable. When I woke up, I was still flooded with that sense of fear. If that is what my parents grew up in, I can see, at least a tiny bit, how miserable that must have been.

In any event, on that particular afternoon, my father went to get my grandfather. However, he took us with him. When we got to the club, instead of going downstairs into the bar himself to get my grandfather, he sent us down. Kids.

First of all, you don’t send kids to do an adult’s job, no matter how much you may hate it. Second, it’s illegal for kids to be in a bar. But Dad didn’t care. He just sent us.

So, I led the way. I was familiar with the club because we went there a lot for Christmas parties and other functions in the upstairs community room. And we’d also been downstairs, but always in the back room behind the bar. It had booths, a jukebox, and a window shelf where we could order soda and pretzels, and such.

I headed down the stairs to the locked door. Thinking about it, I have to laugh. It was like one of those mysterious 1920s speakeasies in that you had to knock on the door and wait. Somebody would open the little eye slot, peek out, then decide if you could come in. And true to form, that day when I knocked, the slot slid open and I heard a deep voice say, “It’s okay. It’s John’s kids.”

The door swung open, and they all welcomed us in. Being late in the afternoon, things were kind of relaxed. A few old men were still at the bar, including my grandfather. They immediately started buying us sodas and ice cream, pretzels, and potato chips, and gave us money to play the arcade games.

My favorite was the table shuffleboard game with the metal discs that you had to carefully slide across a polished wooden table. The goal was to get them in the scoring zone at the other end of the table, without dropping them into the box off the end of the table.

So between the soda, snacks, and games, I was all set and started playing. I don’t know how much time passed, but eventually my father realized none of us were coming out. So he ended up not only coming to retrieve his father-in-law, but his kids, too. Serves him right.

Grandpa’s days of doing this, however, came to an end in the mid-1960s. For one thing, he developed Type II Diabetes. He had not been feeling well and he had to start taking medication and change his diet radically. The other was the devastating loss of his daughter, Sister Luke.

For certain, he was a quiet man all his life. But underneath that quiet, was a deeply emotional man who truly embodied that sense of “still waters run deep.” She was supposed to come home for a visit that summer of 1964, and he was eagerly looking forward to it. Then she was not able to come. I’m told he was very upset. And unfortunately, he never got to see her again. She died in that car accident in March of the next year. I think that loss really aged him. In all his pictures after that, he never seemed to smile again.

The dog

As part of his revised diet, Grandpa had to limit his sugar and carbohydrate intake. So the best he got for beer was something called “Dia-Beer,” and his afternoon snacks were usually plain crackers.

Sometimes our dog, Sandy, would go upstairs to visit him. She would sit out in the hall and just wait until someone came to the door. I would hear my grandfather open the door and say, “Sandy! Why didn’t you bark? Come in!”

Then Grandpa would rinse the salt off his crackers and give her a few. She would eagerly eat them up. And he was the only one who could get her to do that. If any of us had offered Sandy crackers, she would have turned up her nose to them. But from Grandpa, she treasured them.

As with the bird, Grandpa loved our dog. The one time my grandfather actually yelled at my father, it was over the dog.

One Sunday morning, my father had taken the dog to our property but wasn’t watching her. She ran into the road and got hit by a car. He had to rush her to the vet’s, where she stayed for a few days before she could come home. My grandfather was livid and let my father know it. It was the only time I ever heard him yell.

What did he know, if anything?

I have often wondered what he thought about Dad. Just because Grandpa didn’t say much doesn’t mean he didn’t notice things. I can’t imagine he didn’t hear the fights or see my father tearing out of the driveway afterward. And, I still wonder if he didn’t actually see my father that time, molesting me on the couch in our apartment. Or at least notice that the energy of the whole interaction was weird.

As a kid, I thought no one knew what went on in our house. But as an adult, I realize a lot must have been observed. My great-aunt would occasionally make a polite but sharp dig at my father, knowing that he wouldn’t dare pick a fight with an old lady. It would damage his image. So, I suspect she knew more than she let on.

I also know that the rules of the Catholic church and Slovak culture dictated that a couple married for life, the man rules, and you don’t interfere between a husband and wife. So, maybe they all had to just keep quiet. But maybe there were other factors in this, too.

Grandpa was no fool. He’d worked in factories and on farms, no doubt with a whole range of personalities, from the kindest to the outright mean. I’ve wondered if he read my father better than anyone knew.

Being older and no longer physically healthy, could he have confronted my father? I don’t think so.

Did Grandpa fear my father? Either for himself, or for what he feared Dad might do to us if he fought with Dad about it? I think so.

That snowblower that Grandpa loved so much? During one particular snowstorm, he and my father got into an argument over it. My father told him he was too old to be out there doing that, and frankly, he was pretty nasty about it. My father emasculated and demeaned him. To his death, my grandfather never touched that snowblower again.

And for anyone who thinks it’s easy to stand up to an abusive person or check his power, guess again. Speak up and set that person off, and you may put yourself or the other family members in physical danger. They may not have known this as “abuse,” but they probably knew not to poke the bear.

Could anyone in that house have checked Dad’s physical violence? No.

The house

The other thing was that recently, I came across was a website with the original mortgage-paper records for that house. I was looking to verify what year we actually moved in there. When I saw the signature page, before I could even form a conscious thought, my gut reacted. Shock, followed by, Of course.

Yes, my grandfather’s signature was there, but so was my father’s. He co-signed for the mortgage. In all those years, I never knew that. I don’t know if my mother even knew.

But it makes sense that with my grandfather being older when he applied, and not having much money, the bank must have insisted on a co-signer before letting him buy the house. And there was my father to “help out,” I guess.

Maybe that’s all it was. At that point, it might have seemed like a really good idea for everybody. My parents would have a place to live, owned by her father, and the rent would help pay the mortgage. It provided a secure thing for everyone.

But I also know that my father never did anything without looking for his angle in it. And he had that motto of if you want someone to like you, find out what they need and give it to them. Well, Grandpa needed a co-signer, and my father filled that role.

My father then, was the physically dominant force in that house. And at the very least, he had the potential to be the financially-controlling force as well. Maybe we weren’t the only ones silenced. What do you do when everyone’s very security of place, their home, rests in the hands of someone with more power than you?

I also wonder if, a few years later, as my father wanted more out of life — property, a bigger house, more things — that the early decision to co-sign the loan didn’t prevent him from pursuing those dreams right away? Did that become a trap for him, a source of frustration and rage that he vented at my mother?

I remember that she mentioned the excuse about Dad wanting to build a house and being stuck in our apartment. That was also the time he seemed to demean my mother more and push her to go get a job, when earlier on, he wanted her home.

I cannot prove anything. I have more questions than answers. And just my observations of patterns and people’s behaviors. But I also know the emotional reaction in my gut when I saw my father’s name on that mortgage. All I could think in that moment was, Of course. Dad had physical power. Possibly financial power. Who would or could stand up to him? Checkmate…

Leave a comment