He’s waiting

Every Saturday, He was there, waiting for me. The door would close behind me, wrapping me in the silence and darkness. And He would be there, waiting, watching, silent.

Guilty and scared, I would glance up at the life-sized crucifix in the vestibule, then look down. I couldn’t tell if I was being viewed with compassion, like He understood my “predicament,” or disappointment, because yet again, I failed Him.

Why couldn’t I have a dad who didn’t do these things? Why couldn’t I have a body that didn’t even have these kinds of feelings? It could be so easy to go to heaven if you could just focus on other things in life and never on “that.”

I looked over at the bookstand and wanted to see if there was anything new. But right now, I was too upset. After.

The agony of the choice

Before I’d even gotten here, I’d gone through the agony of the first decision: Do I even go to Confession today? And, if so, which church do I go to?”

I could go to my church, feel the heaviness of my sins, and have the same old priest. Or I could go to the other church downtown. At least it was brighter there…I felt less like a sinner there. And they had 3 different priests, none of whom knew me. Maybe they would tell me something different?

To this day, around 3 p.m. on any Saturday, I feel the same sense of tension and heavy shame, laced with tremendous anxiety, even though nothing in my current life accounts for that. It is the echoes of that confessional box.

About Confession

It was standard practice in the 1960s that at age seven, you made your First Confession, and then First Communion. At that age, you were then held responsible for following all the rules about “avoiding the near occasions of sin,” as the catechism called it.

And let’s be clear. Confession wasn’t ever really about how many times I talked back to my mother. The Catholic church was first and foremost concerned with sins about “that,” which meant anything even remotely sexual. Avoiding the “near occasions of sin” was all about “Did you avoid those ‘impure thoughts and deeds?’”

And this emotional shaming started at seven. Author John Cornwell, in an article for the Daily Mail, noted that the Jesuits had a line that Pope Pius X must have had in mind when, in 1910, he made it mandatory for all children, aged seven and older, to participate in Confession: “Give me a child at seven and it’s mine for life.” The pope also wanted everyone, including children, to be confessing weekly.

John Cornwell wrote a book on the subject, entitled The Dark Box – A Secret History of Confession. In it, he noted that forcing such young children into confession was a radical change from pre-20th-century doctrines that did not allow children to make Confession until their teens. He went on to say that this decision was to “prove calamitous for generations of young Catholics. Childhood confession prompted complexes about sex and unwarranted guilt, and catastrophically, it created ideal opportunities for pedophile priests.”

Even taking the risk of child sexual abuse in the confessional box out of the picture, the trainings taught young children that “…sins which broke the ten commandments or the Church’s rules were ‘mortal’…and earned punishment in the eternal fires of Hell.”

And Cornwell further noted that the “dominant topic of the moral textbooks” used by priests training to hear confessions was sexual sin:

“Immodest acts, however slight they may be, that are done from the motive of exciting lust…are grievous sins.” H. Davis, *SJ, Moral and Pastoral Theology*

Cornwell stated that the manual spent five pages on the sin of masturbation, gave only a third of a page to rape, and made no mention of child sexual abuse in ANY of the four volumes of that manual. He went on to note that “…Masturbation is the subject of the most keen, obsessive, and extensive discussion and analysis in the manuals.”

So, with this as the background for 1960s Catholic dogma regarding sin, my Saturday-afternoon dilemma was multi-faceted. First, there was the fact that just on general principle, I was a sinner and that put me at risk of hell. A terrifying prospect. And of course I was a sinner. The Church was always reminding me of that in every prayer.

Then, I was guilty of those “grievous sins” listed in the moral textbooks, the infamous “impure thoughts and deeds.” Name one human being who isn’t, including the priest I was confessing to.

And then, there was “that sin,” the one with Dad.

Given all of this, it goes without saying that being in that dark box, kneeling before a priest, and having to either answer his prying questions or proactively admit the “sinful” things so as to avoid going to hell, inflicted a tremendous amount of anxiety, anguish, and shame on any child.

My own Saturday Confession experiences

I hated going to confession every Saturday but I was too afraid not. Between guilt about what Dad was doing to me, and fear of going to hell, I had no choice. And I was afraid of God, and of the priest telling me I was at fault. Or that out of shame or fear I would avoid telling the priest, thus making my confession null and void. In short, for so many reasons, I was just afraid. And ashamed. So, I went to confession.

Years later, as a parent, I looked back and wondered why my mother never questioned that her 7-8-10-11-year-old compulsively went to confession. If that had been my child, I would have been asking a lot of questions and checking to see what could possibly be so wrong. But in an interesting twist, toward the end of her life, my mother was going to confession almost weekly, and I wondered what could be so wrong for her….

Alone in the dark

The back of the church was always dark, even during Mass with lights on, just because it was under the upstairs balcony. But on confession days, it seemed even darker.

Yet, at the same time, I was grateful for that. It was a cocoon. A blanket that made it hard for anyone else to see me if they were there. I could pull within. Be alone with my thoughts. With God. And, it felt right for a sinner to be covered in the blanket of darkness.

Looking back, I should have been scared being alone when I got there. Even then, and maybe more so now, people have been attacked when alone in a church. But I felt better taking my chances there. Home or church, what was the difference? And at least if someone came in and it seemed “off,” I could bolt out one of the doors. At least here, I stood a chance of being left alone.

The “lineup”

I liked to get there early, so I could go first. If you didn’t arrive until right at 4:00 p.m., there might be several others ahead of you. It was hard enough deciding to come, but to have to wait for others before I could have my turn would be sheer agony.

The Rules of Confession and the Decision Tree

To be forgiven, you had to make a GOOD confession. The Baltimore Catechism used those exact words…a Good Confession. And it listed three qualities that were key: “No excuses. No falsehoods. No omissions.”

To achieve a good confession, it set out very specific rules:

- Examine your conscience

- Remember when your last confession was

- Collect your list of sins and how often you did them – yes, it had to be quantified to show how grievous you were

- Decide if your sins were mortal or venial

- Make an act of Contrition…a good one…and TRULY be sorry

- Promise not to do it again

- FULLY confess everything to the priest – no holding anything back. Unspoken sins don’t get forgiven. It’s not “batch penance,” and they’re not grandfathered in with the rest.

- Receive absolution from the priest

- Say your penance

At this point, you were back in a state of grace, which would be a relief to me. It meant if I got hit by a car on the way home and died, I would go right to heaven because I wouldn’t have had a chance to “sin again,” yet.

I knew the whole routine since I came so often. And most of the steps I was happy to do. But the struggles always came down to steps 4, 6, and 7.

Step 4: Did I have mortal sins? If I did and died, this was a straight trip to hell, forever. So I wanted to be sure to either rule out any mortal sins or confess them.

For a sin to be mortal, you needed three things:

- It had to be serious…But define “serious”?

- You had to KNOW it was serious – Well, that was the issue, wasn’t it?

- AND you had to choose to do it anyway. There was no question on that one. With Dad, I had no choice. And even just on my own, there was always that “urge” that seemed impossible to ignore. Why did God make bodies like that, anyway?

About the sin with Dad, I always ended up giving in, even when I tried to avoid him as long as possible. Eventually, I’d have no choice. But still. I let him. A true martyr for the faith, like St. Tarcissius, wouldn’t have given in. So wasn’t I to blame?

And then, was it SERIOUS? I thought so. At least it felt horrible. Especially if Mom ever found out.

But the fact that I wasn’t sure could be my out in this. After all, for the sin to be mortal, you needed all three things. If I wasn’t sure, then it was only one or two. And one or two out of three didn’t count.

Step 6: Promise not to do it again. Of course, I didn’t want to do any of it again. Not with him. Not on my own. And I always tried, but I always failed.

Step 7: Make a full confession. That was the final issue. WHAT did I absolutely HAVE to say to get credit for this confession and have my sins forgiven?

I knew that if it was venial, I could be vague, get absolution, say my penance, and be back in God’s grace. And also, if I forgot a sin, that was okay…THIS time. Though I’d have to tell it the next time or else. But forgetting “those” sins was unlikely. They were ALWAYS on my mind.

But if it was mortal, I would HAVE to say it…clearly. If I were vague or held back, then not only would the Confession be null and void, but I’d also get an extra mortal sin on my soul because that would be a BAD confession. While the priest might not know I held something back, God would. And so I would still be damned to hell. A couple of times over.

Decision Time – Go or No Go

So I sat there, sometimes in a cold sweat, agonizing. Grilling myself mercilessly to be SURE of my motives if I decided nothing was a mortal sin. I didn’t want the easy way out. I wanted the truth. But if it wasn’t mortal, why inflict extra anxiety on me?

Glancing at the clock, I get more and more tense. Once the priest walked into the church with that purple stole vestment around his neck and stepped into the middle booth of the confessional, it would be “Go time.” I’d have to know what I was going to do.

The Act of Contrition

One of the most important things was to say the prayer: The Act of Contrition. And you needed to make it a good, heartfelt one. On that count, I always did. Seven decades later, I still remember it, word for word:

Oh my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended Thee. And I detest all my sins because I dread the loss of Heaven and the pains of Hell. But most of all because they have offended Thee, my God, who art so good and deserving of all my love.*

*I firmly resolve with the help of Your grace to sin no more, and to avoid the near occasions of sins. Amen.

There it was. The promise of sinning no more and those damned near occasions of sin. But in that moment at least, I really did want to live up to this.

The thing I’ve wondered since is that God knows we are all imperfect humans. So promising something you couldn’t do, then having to come and admit that every week seemed like setting you up for failure. Rubbing your nose in your imperfect humanness. Making you feel even worse because you never succeeded. How was this supposed to be uplifting for my immortal soul when all it did was depress me?

In the Dark Box

The closer to 4:00 p.m. it got, the more frequently the heavy church door would creak open. Others were arriving for their confessions. But everyone knew the rules. If others were there, lined up in the pews ahead of you, then you didn’t jump the line. You waited for your turn. At 4:00 p.m., almost on the dot, the door would open, and this time, the priest walked in.

The priest. The person designated by God to have the power to forgive your sins or not…the ultimate power to damn your soul to hell or to bless you. To disapprove, lecture, and destroy you emotionally.

He would walk to the confessional, which was set back into the darkest corner of the church, and step into the middle booth. On either side of him was a chamber for the “sinner” to go into.

My heart would be pounding from the moment he came in.

Once he was tucked into his spot, two of us would walk toward that dark box, one entering on each side of him. Drawing the heavy maroon curtain aside, I could see the kneeler set up to face the side wall toward the priest. The curtain would drop back into place, and the chamber would go black for a moment as my eyes adjusted to the space.

Kneeling down and folding my hands, I waited in the silence. Two people, one on each side, both tense, waiting to see which side would get to unburden themselves first. Whichever window’s little door panel opened, that was the “lucky” one.

More times than not, I seemed to get second place. The waiting was agony, wrapped in a darkness that seemed almost impenetrable. Beneath my knees, the pad felt too thin. My heart pounded, and my ears strained to pick up any sounds that would indicate it was my turn.

Total quiet. That meant the other person was talking.

Then the priest mumbled something. Was he giving out penance already?

No. Instead, there was more back and forth as silence alternated with mumbling.

I stared hard at the little holes in the plastic plate in front of my face. But behind it was still the closed, dark wooden door.

My heartbeat sounded like explosions in my ears.

A noise.

The priest was talking again. Penance finally?

A little louder, Latin. Good. That was the absolution and blessing.

Almost time for me.

What will I tell him?

I heard a rustle and some noise on the other side. The other penitent was leaving.

At the same time, the small door panel rattled open, and I almost jumped off the kneeler.

He blessed me, and then it was my turn.

I started. “Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. It’s been one week since my last confession.”

Deep breath of hesitation. I cleared my throat.

“I talked back to my mother…three times….I took the name of the Lord in vain, once….

I…uh…was thinking about… things…and…

Most times, I had decided that I wasn’t guilty of mortal sins. So I would lump things into the usual “impure thoughts and deeds.”

But there was one day…I drew up all my courage. I so wanted to describe what Dad was doing. The words rose in my throat…and stuck there.

I finished my confession, took my penance, and left.

I figured I was blessed enough not to go to hell. But…I wanted a priest to help me. To understand. Advise me. So, the next week, I went to the church downtown. The church with the three priests. They were younger. At least a little younger. Surely they might understand. And could help.

Again, I ran through the usual sins and then hesitated. The priest asked if there was anything else. Drawing in a deep breath, I said yes and started to describe what my father was doing to me. Before I could finish or ask for help, he told me, “Don’t tempt your father.”

I was crushed. There it was…I WAS at fault. What was I going to do? I couldn’t tell Dad no because I’d pay for it. But I was at fault. It was my sin for giving in. Even Dad had said one time in the car that men were weak and women had to be the strong ones to keep them in line. So…I was failing.

Not being one to give up, a few months later, I tried again to talk about it in confession. I went to that same church and picked a different priest. But again, it was MY fault.

I never spoke of it in confession again, until several years later, as a young adult. This time, I drove to Farmington, a town about a half-hour from Torrington. There was a monastery there. My father had gone there for retreats with the church’s men’s group.

One particular time when I was in my 20s, he went for the retreat and was actually scared. For whatever reason, after all the years of abusing me, he suddenly wondered if he was doing something terribly wrong. I felt SUCH hope that this was God FINALLY answering my prayers. Finally getting through to Dad that this really WAS wrong and had to stop. For the first time in my 20+ years of life, I finally felt HOPE.

It was all to no avail. The monks apparently reassured him that he was a good man and to stop being hard on himself. I have no idea if he was honest with them. But it didn’t matter. He came back, totally relieved and very happy…and started in on me again.

So I went to that monastery. I figured if they could make my father feel better about himself, then surely they would have some way to help guide me. This was the third time I was trying to find a priest who could help me with this situation. The outcome? “You shouldn’t tempt your father.”

I was absolutely devastated. I wasn’t tempting him. Just trying to stay sane and survive in my house. But…three different priests at three different places at three different times in my life, and always the same answer.

I gave up after that. I just fell into a deep despair that I will talk about later.

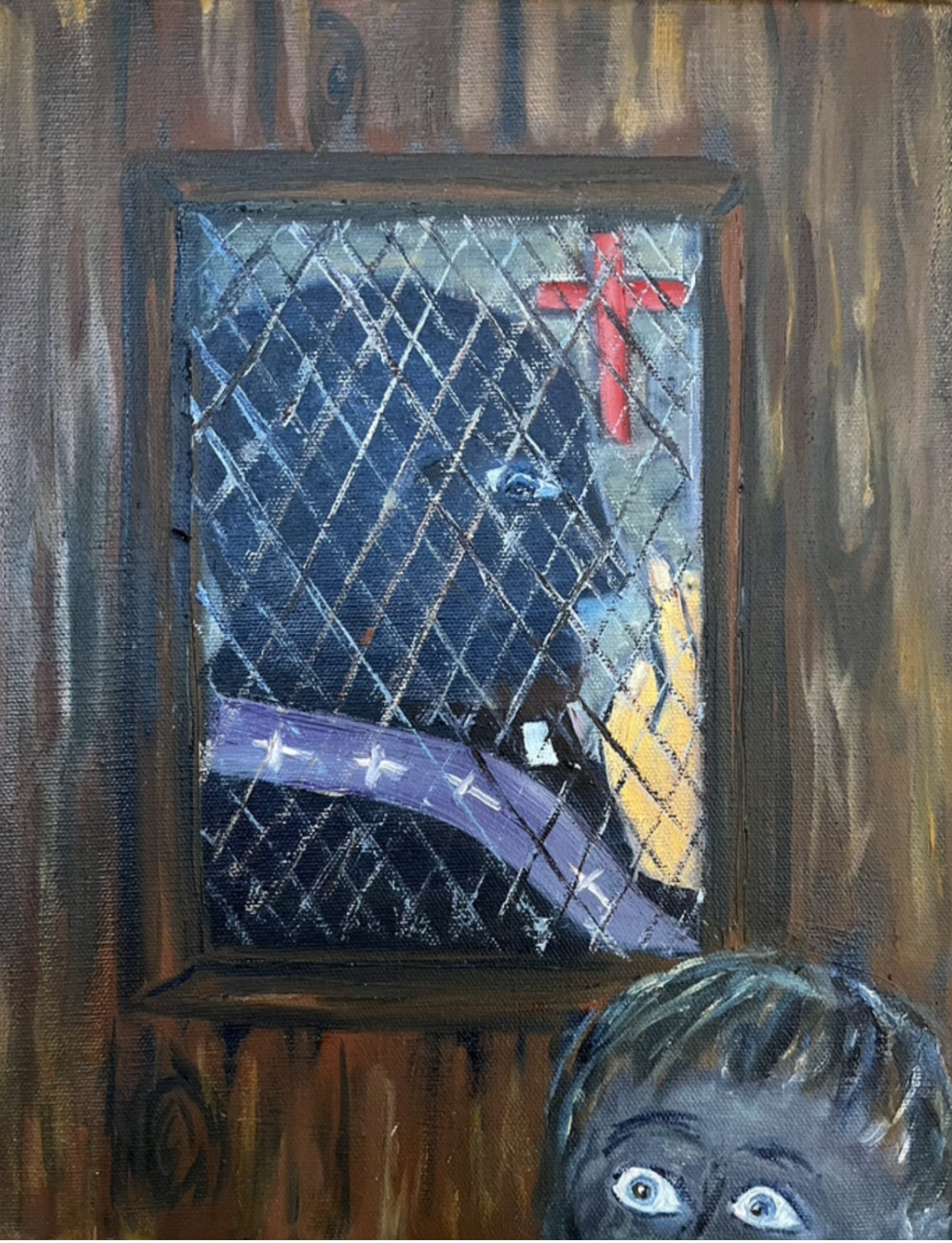

In my painting above, I tried to capture the emotional experience of that dark box. Even as I knew that if the priest was waving his hand, it was to pronounce the absolution blessing, it also felt more like an admonition…or a threat. “Don’t do that anymore!”

A friend looked at the painting and said it looked like the priest was telling me, “Sh-h-h-h… be quiet…don’t tell.” Like I was to stay silent and not speak the truth. Certainly, that was the rule in my house.

No matter what it meant, I knew that his raised hand was the all-defining moment. Patriarchal, ecclesiastical power at its peak. All about “Will he or won’t he grant me that all-needed precious absolution?”

Years later, there were whispers in town of a priest at that church downtown, pulling altar boys from class and taking them to the rectory…about angry parents, and demands to the bishop….”

No matter how confession turned out at my church, there was one comfort I could always count on…Mary….

Next – Visiting with Mother Mary

Leave a comment